What is a file? Link to heading

Files, everything is a file! You may have heard this phrase in relation to Linux. It’s quite popular among Linux enthusiasts, but beyond being a catchy sentence, what does it actually mean?

To understand this, we first need to define what a file is at its core. Not necessarily a digital file, but the concept of a file.

A file is a thing that holds information, and with which you can interact to access that information. How do you interact with it? Think of a notebook. You can pick it up and open it, read it, write in it, erase something that was written, and eventually close it. With this simple set of actions, you can do even more: you can make copies of your notebook, create new notebooks, or share your notes with others—and they can share theirs with you. You can do a LOT with this thing that holds information.

Considering these basic interactions, open, read, write, and close and how universal they are, the creators of Unix came up with the brilliant and simple (it’s amazing how often these two qualities go hand in hand) idea: why not treat everything as if it were a file, and use the same set of APIs for all these tasks? And that’s exactly what they did!

File Descriptors Link to heading

This universality in the API is made possible by implementing something called file descriptors. These are unique integers for each process, used to represent files or I/O resources. They allow system calls to interact with resources by telling the kernel how the process intends to access the file. There are 3 file descriptors in the POSIX API:

| Integer | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Standard Input (stdin) |

This is a stream from which a program can read input data using the read operation, like when reading input from the keyboard. |

| 1 | Standard Output (stdout) |

This is a stream where a program writes its output data using the write operation. While not all programs generate output, when they do, it’s typically directed to a specific location, such as a file or the text terminal in the case of an interactive shell. |

| 2 | Standard Error (stderr) |

Similar to stdout, this is also an output stream, but it is specifically for displaying error or diagnostic messages. Being independent of stdout allows us to handle its stream separately. |

Is my red blue for you, or my green your green, too? Link to heading

“How do I know that you and me

See the same colors the same way when you and me see?

Is my red blue for you, or my green your green, too?

Could it be true we see differing hues?”

- in Thoughtful Guy, by Rhett and Link

Besides being a cool verse and a deep philosophical question, it’s also something we need to ask about files: Does the OS see files the same way I do?

As for the colors, I have absolutely no idea, but when it comes to files, the answer is no. For the OS, a file is represented as an inode, a structure that holds metadata about the file. This includes the creation date, last update date, ownership, permissions, size, and most importantly, it contains a pointer to the memory block where the file’s actual data is stored.

To see all the information stored in an inode (and more), you can simply use the command ls -il. Let’s try it!

remnux@00cd6cd99d6f:/var/log$ ls -il

total 1824

37128568 drwxr-xr-x 4 remnux remnux 4096 Mar 10 2023 networkminer

Let’s go through what e see here from left to right:

- First, we have the inode number. This number is indexed in the file system’s inode table, and with this index, the kernel can access the inode’s content and the file’s location, allowing the kernel to retrieve the file.

- Next, we have a list of characters and dashes, which represent the file’s type and permissions. If you’re reading this, you probably already know what they mean, but let’s go over it just in case:

- The first character indicates the type of the file. There are 7 types (we’ll dive into these in more detail later, but here are the options):

- - Regular

- d Directory

- l Symbolic link

- b Block

- c Character

- s Socket link

- p FIFO (Named pipe)

- The next three characters (in our case

rwx) represent the owner’s permissions. - The following three (

r-x) represent the group’s permissions. - The last three (

r-x) represent the others’ permissions.

- The first character indicates the type of the file. There are 7 types (we’ll dive into these in more detail later, but here are the options):

Permissions follow a simple representation standard: r stands for read, w for write, x for execute, and - for no permission.

They always appear in the same order—r, then w, then x—because this is tied to a binary representation of three bits, where each character is represented by a 1, and a - is represented by a 0. What does this mean? It means that rwx is equivalent to 111 (or 7 in decimal), and r-x is 101 (or 5 in decimal). When we combine all three sets of three characters, a file permission like rwxr-xr-x can be represented as 755.

- Next, we have the number of hard links to this file. Links are quite interesting, and something I think you’ll enjoy reading about. But just to be brief, did you notice I didn’t mention the name of the file as part of the metadata held by the inode? That’s because a file doesn’t actually have a name; it is linked to one instead. A hard link is a file representation of this association between the file content and its name. All files will have at least one hard link (this happens because things like directories exist, and we’ll touch on this subject later).

- Owner name.

- Group name.

- Number of bytes in your file (size).

- Date of the last modification.

- And the name of the file (which we already know it’s not in the inode)

For more information about a file, you can also use the stat command, which will give you details like when the file was last accessed, modified, and created, its IO Block, among other things.

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:/var/log$ stat alternatives.log

File: alternatives.log

Size: 63157 Blocks: 128 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: 32h/50d Inode: 37128551 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2023-03-10 04:07:39.000000000 +0000

Modify: 2023-03-10 04:07:39.000000000 +0000

Change: 2025-01-31 09:39:34.999892789 +0000

Birth: -

What types of files are there? Link to heading

Now that we understand the concept of what a file is and how a file is treated by the system, we need to narrow down the types of files there are. Because although it’s very cool to say everything is a file, we need to understand how big this everything really is and what we can expect to encounter.

In reality, everything means seven, which maybe isn’t as big as you thought, but it’s still more than enough, trust me. These standard Unix file types are defined by POSIX, although specific OSs can define their own beyond these. But leaving that aside, let’s take a look at each one.

Regular Link to heading

These are the “common” files that you typically think of as quintessential files. These can be anything from scripts, images, videos, audios, compressed folders (zip, 7z, …), documents, program-specific-format files like XML, DOCX, PDF, and many others.

Because files can be so many things and hold so many types of different information depending on their use, Unix does not impose or provide any specific internal structure for this regular file type; this is entirely up to the program using them.

As we discussed before, regular files are identified by a -, as we can see in the example below as the first character.

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:/var/log$ ls -l

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 63157 Mar 10 2023 alternatives.log

But if you want to know what a file is, well, although there is no imposed structure, there are always conventions, standards, and programs that are so universally used that even if you don’t recognize it (or it is hidden from you!!), the file command will usually be able to tell you what type of file it is.

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:/var/log$ file alternatives.log

alternatives.log: ASCII text, with very long lines

This works because of something we call “magic numbers” or more appropriately, file signature, which are unique sequences of bytes at the beginning of a file that indicate the file format. The file command reads these magic numbers and compares them against a database to determine the file type. This database is typically found in /etc/magic or /usr/share/file/magic.

Magic numbers and file signatures are an interesting and important subject, especially regarding forensics and malware analysis! Maybe I’ll write a post about them someday, but you should definitely read about them.

Directory Link to heading

Yes, a directory is a file. In fact, it is the most common “special” file of all files. But since it is a file, and files store information, what does a directory hold?

Well, it can’t hold other files as a whole. If that were the case, then all files would, in fact, just be a single file! It would be like saying that if we wrote an entire book on a single page, it would still be a book because it holds the same information as if it were written throughout various pages, which wouldn’t be true.

Remember before when I said a file doesn’t actually have a name, it’s just linked to one? That link is what a directory holds.

A directory is a file that actually only contains a mapping table, linking all its child files (of all types) names and their respective inode numbers. Returning to the book example, a directory is like the index. It doesn’t tell you the information of each chapter, but it tells you the chapter’s name and the page it begins at. That chapter’s name is unique in that book. It may exist, in other books, chapters of the same name, but they are not the same chapter since they do not exist in the same book. This means that file names are directory-specific, and that is why they are not held in the inode!

Can you imagine if every file name had to be unique system wide? I’m not that imaginative!

Symbolic link Link to heading

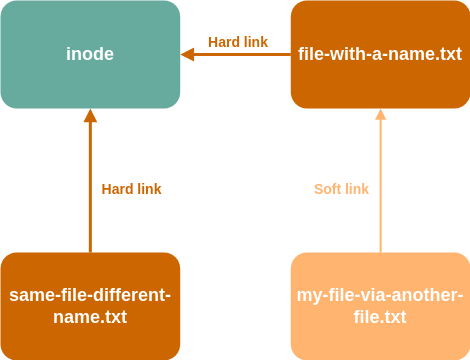

We have hard links, but we also have symbolic links (also called soft links), and it is nothing but a reference to another file.

But what is the difference, you ask? Well, first of all, a symbolic link is a file in itself and thus it holds information, unlike a hard link. This file holds a textual representation of the file’s path it references.

Unlike hard links that tie a file’s name to its inode number, the soft link is a link to the file name, which is then linked to the inode via a hard link. Because of this, if you delete or move the original file, the symbolic link becomes useless (dangling) as it is pointing to a path that now has no file.

Yeah… confusing… just look at the image!

Turning back to the shell, symbolic links are denoted by a l character, and depending on the OS you’re running, some have a handy representation showing you which file they are referencing.

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:~$ touch file-with-a-name.txt

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:~$ ln -s ./file-with-a-name-txt my-file-via-another-file.txt

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:~$ ls -il

total 0

36178073 -rw-r--r-- 1 remnux remnux 0 Feb 6 15:38 file-with-a-name.txt

36178076 lrwxrwxrwx 1 remnux remnux 22 Feb 6 15:40 my-file-via-another-file.txt -> ./file-with-a-name-txt

36178073 -rw-r--r-- 2 remnux remnux 0 Feb 6 15:38 same-file-different-name.txt

remnux@25bdfcf5df91:~$

Notice a cool thing in the previous code snapshot. Did you notice that the file-with-a-name.txt has 0 bytes, but the symbolic link file, my-file-via-another-file.txt, has 22?

Try counting the characters in the name of the original file ;)

FIFO Link to heading

FIFO are quite interesting and fun files. One of the strengths of Unix is the capability of processes to communicate with each other, and one of the ways they do it is by using pipes, which direct the output of one process to the input of another process. But for a file to be able to use them, they must exist in the same parent process space, started by the same user. But what if you want processes from different users and different permissions to communicate? Well, here comes FIFO to the rescue!

FIFO files, or named pipes, can be created anywhere in the system and function like a “dropbox for data streams.” One process writes a value inside, and another can go in there and read it.

FIFO files can be created using the mkfifo command, and they look like regular file system nodes but are distinguished by a p character when you use the ls -l command.

When a FIFO is opened for reading, the process will block until another process opens the FIFO for writing, and vice versa. This means they are unidirectional! Data written to a FIFO is passed internally by the kernel without being stored on the filesystem.

You can do some interesting things with named pipes. Let’s see it.

- First we create the file

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# mkfifo pipe

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# ls -il

total 1824

...

36452964 prw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Feb 6 22:28 pipe

...

- Then we need to execute something that outputs a stream of data, like the

lscommand. But remember, named pipes are blocking, so you need to push it to the background; otherwise, you will be stuck until another process (like acat pipeon another terminal) reads the pipe.

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# ls > pipe &

[1] 37

- Now that we have the pipe as being “filled” with data on the “writing side”, we need to read it. But once again, remember once we open it for reading, it will block until something is written on the other side! You may not notice this as a problem if what is being written is from an “endless” source, like a ping or

/dev/urandom, but if it’s not and you happen to try to read it when there’s nothing more to be written on the other side, you’ll be stuck in a blocked process. One way to avoid this is to direct the pipe read to a file descriptor which we can then read without getting blocked.

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# exec 3< pipe

- Now, you can just read the file descriptor!

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# read -ru 3 abc

[1]+ Done ls --color=auto > pipe

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# echo $abc

alternatives.log

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# read -ru 3 abc && echo $abc

apt

root@1f587f78be08:/var/log# read -ru 3 abc && echo $abc

bootstrap.log

...

Notice how the first read operation unblocked the writing process, allowing it to terminate, and also, that in this specific case, it is reading the output of

lsline by line.

Soo yeah, named pipes are a bit weird when it comes to files, and you’ll probably very rarely find one in the wild like this, but nevertheless, now you know!

Socket Link to heading

A socket is a unique type of file used for inter-process communication, allowing two processes to exchange data in both directions (duplex communication). In addition to sending data, processes can transmit file descriptors via Unix domain socket connections using system calls like sendmsg() and recvmsg().

Sockets are identified by an s at the beginning of the mode string when listed in the file system.

So far, we’ve covered creating various file types, but sockets are a bit different. Unlike regular files, you can’t just create a socket and leave it sitting there — it needs to be bound to something before it can be used.

You could create a socket file with Python, like you see bellow.

remnux@31e1f2a4f25a:~$ python -c "import socket; sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_UNIX); sock.bind('./socket.sock')"

remnux@31e1f2a4f25a:~$ ls -il

total 0

36729100 srwxr-xr-x 1 remnux remnux 0 Feb 7 09:06 socket.sock

But there are also other, more “black magic”, methods to create and interact with sockets. For this, you’ll need two terminals.

- In the first terminal, start

netcatto open a socket and be able to see incoming messages.

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ nc -lk -p 9991

- Now, on the second terminal, let’s bind a new file descriptor to that socket.

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ exec 3<>/dev/tcp/127.0.0.1/9991

- Still from this second terminal, send a message to the file descriptor.

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ echo "Hello, its me..." >&3

- If you now return to the first terminal, you’ll see that you’ve received it.

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ nc -lk -p 9991

Hello, its me...

- But you can also send! Remember, sockets are bidirectional, so still from the first terminal, respond to Adele!

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ nc -lk -p 9991

Hello, its me...

Hi darling

- Adele on the second terminal will be able to see that you’re not ghosting her!

remnux@129708740d8d:~$ cat <&3 &

Hi darling

Device file Link to heading

In Unix, almost everything is treated as a file and has a location in the file system, even hardware devices like hard drives. The exception to this is network devices.

Device files are used to apply access rights to devices and direct operations on files to the relevant device drivers.

Unix distinguishes between character devices and block devices:

- Character devices provide a continuous stream of input or output.

- Block devices offer random access to data blocks.

Disk partitions can have both character and block devices, where the character device offers un-buffered random access to blocks, and the block device offers buffered access.

- A character device is marked with a

cas the first letter of the mode string. - A block device is marked with a

b.

One common place to find character device files is in /dev. And by the way, remember that stdin is a file? Have you tried reading from it?

remnux@8e51daf087af:~$ ls -il /dev/

total 0

...

13 lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 15 Feb 7 10:17 stdin -> /proc/self/fd/0

...

remnux@8e51daf087af:~$ ls -il /proc/self/fd/0

140075 lrwx------ 1 remnux remnux 64 Feb 7 10:24 /proc/self/fd/0 -> /dev/pts/0

remnux@8e51daf087af:~$ ls -il /dev/pts/

total 0

3 crw--w---- 1 remnux tty 136, 0 Feb 7 10:24 0

remnux@8e51daf087af:~$ cat /dev/pts/0

ls

ls

hello

hello

It’s funny how everything you type just shows up again!

To see block devices, you probably won’t find any examples inside a container, but if you go to your host system, you can easily spot them. For example, here’s my nvme drive.

me@host:~$ ls -il /dev

217 brw-rw---- 1 root disk 259, 0 Feb 7 08:41 nvme0n1

Why should I care? Link to heading

Well, this is incredibly important because of what we talked about at the beginning about notebooks: you can open them and read them. This means that if you want to know what something is, what it does, or what permissions it has, you can just open it and read it, or read something that is dealing with it.

Like processes! Although a process is not technically a file, it is represented through the /proc filesystem, which treats processes as if they were files.

For example, you can read the /proc/[PID]/status file to see the process metadata.

remnux@e226bb7dc20e:~$ cat /proc/19/status

Name: ping

Umask: 0022

State: S (sleeping)

Tgid: 19

Ngid: 0

Pid: 19

PPid: 1

TracerPid: 0

Uid: 1000 1000 1000 1000

Gid: 1000 1000 1000 1000

FDSize: 256

Groups: 130 1000

NStgid: 19

NSpid: 19

NSpgid: 19

NSsid: 1

VmPeak: 4132 kB

VmSize: 4132 kB

VmLck: 0 kB

VmPin: 0 kB

VmHWM: 852 kB

VmRSS: 852 kB

RssAnon: 124 kB

RssFile: 728 kB

RssShmem: 0 kB

VmData: 364 kB

VmStk: 132 kB

VmExe: 40 kB

VmLib: 2628 kB

VmPTE: 52 kB

VmSwap: 0 kB

HugetlbPages: 0 kB

CoreDumping: 0

THP_enabled: 1

Threads: 1

SigQ: 0/63458

SigPnd: 0000000000000000

ShdPnd: 0000000000000000

SigBlk: 0000000000000000

SigIgn: 0000000000000000

SigCgt: 0000000000002006

CapInh: 0000000000000000

CapPrm: 0000000000002000

CapEff: 0000000000000000

CapBnd: 00000000a80425fb

CapAmb: 0000000000000000

NoNewPrivs: 0

Seccomp: 2

Seccomp_filters: 1

Speculation_Store_Bypass: thread vulnerable

SpeculationIndirectBranch: conditional enabled

Cpus_allowed: 0000ffff

Cpus_allowed_list: 0-15

Mems_allowed: 00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000000,00000001

Mems_allowed_list: 0

voluntary_ctxt_switches: 62

nonvoluntary_ctxt_switches: 0

Or you can see which file descriptors are opened by the process in /proc/[PID]/fd, or what command was run in /proc/[PID]/comm.

Keep exploring Link to heading

Alright, let’s wrap this up with a little secret: understanding Linux files isn’t just a technical skill, it’s your hidden superpower. Whether you’re diving into forensics or hunting down malware, knowing how files work and how to spot the weird stuff can be the difference between catching a criminal and being left in the dark. From symbolic links that can confuse the heck out of you to FIFOs doing their own little dance in the background, the file system is full of sneaky tricks.

By getting comfy with how files interact with the system, you’ll be ready to uncover those oddball patterns and potential threats that could be lurking in the shadows. It’s like learning the secret language of Linux.

So, the next time you’re diving into a system and looking for those hidden clues, remember: if everything is a file, just READ IT!